What does it mean to be here? Too late. Already gone. Photographs are always of somewhere. Over there. Never here. Normally, they are born and die on a specific date, at a particular time, at a certain place. We gawk at them like corpses in open caskets. Can photographs be more than artificially presented, groomed cadavers of what was once pulsating, undulating, and full of life? There we go again. Gone, gone. Somewhere else.

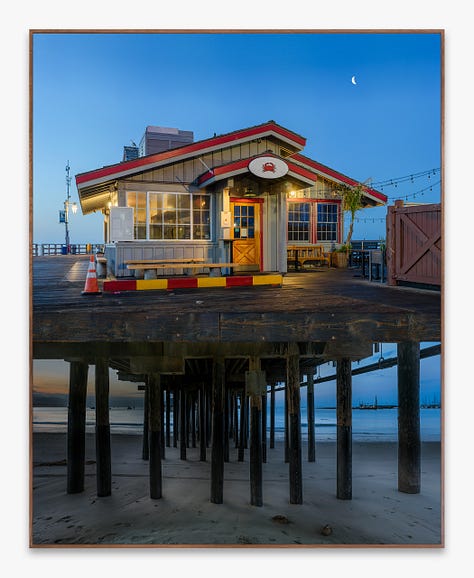

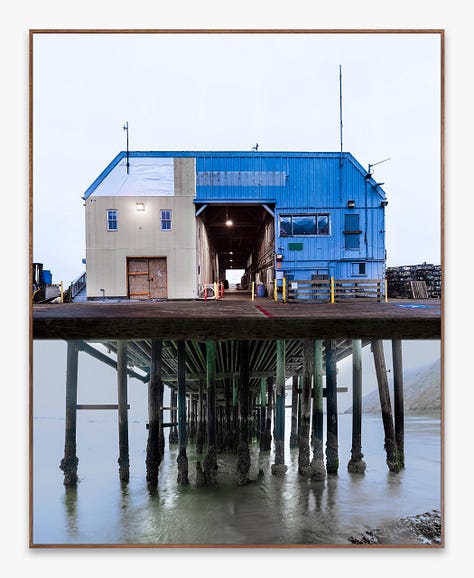

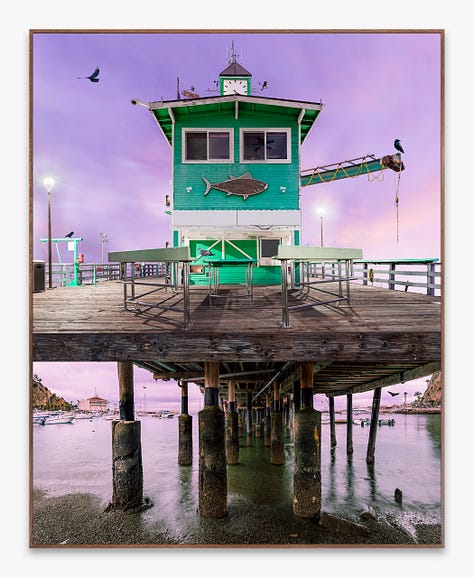

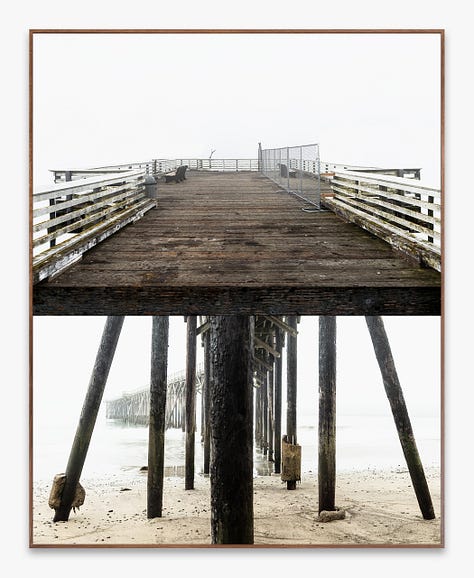

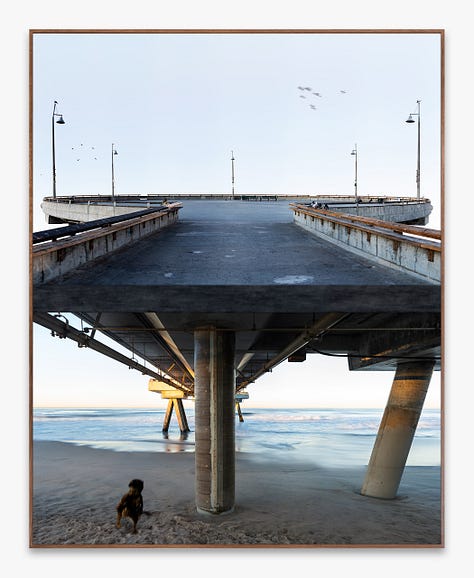

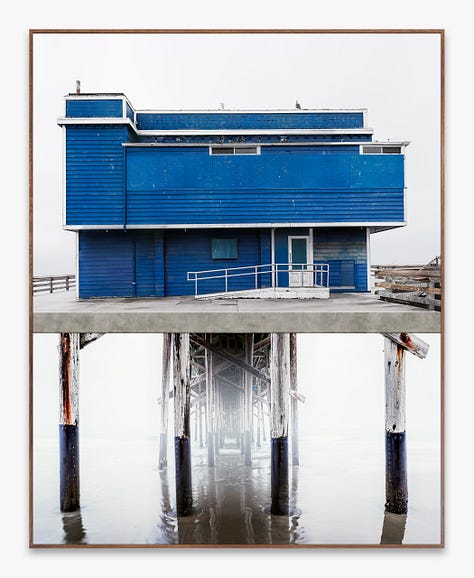

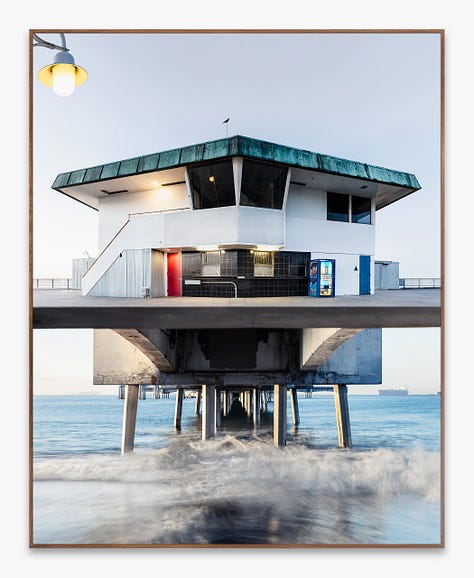

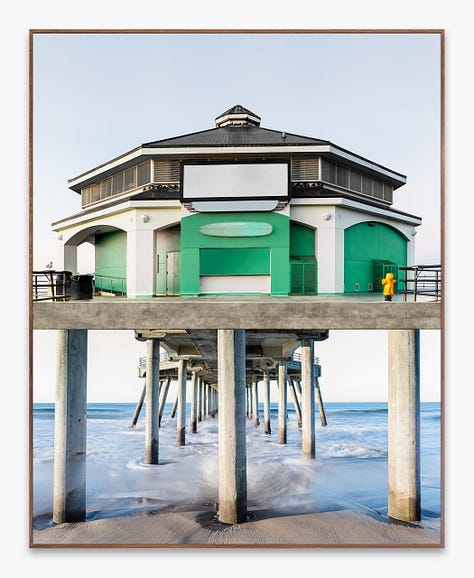

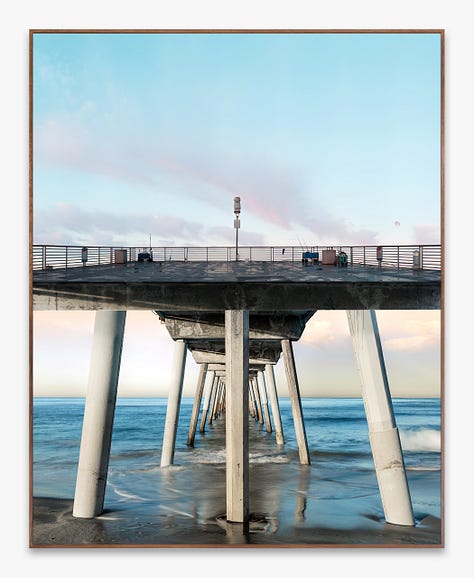

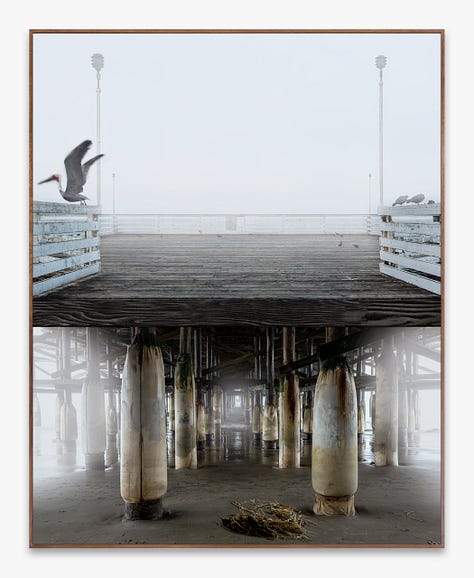

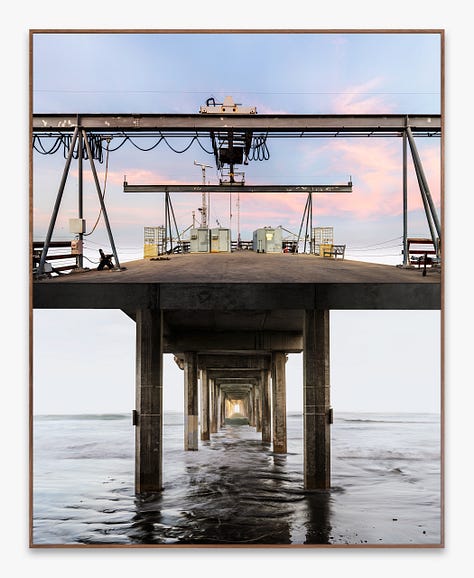

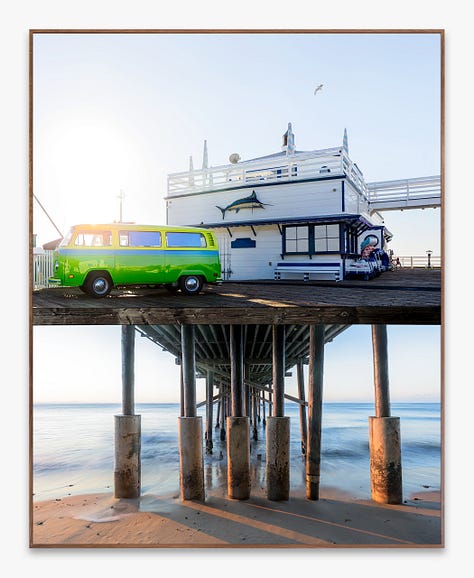

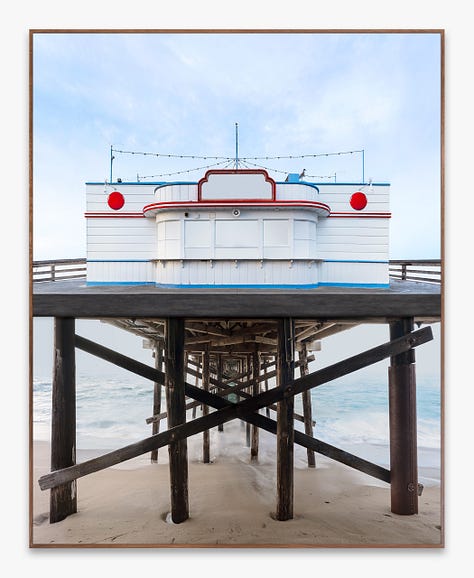

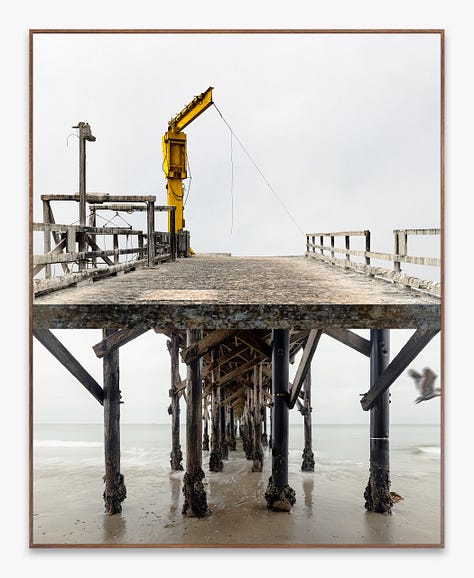

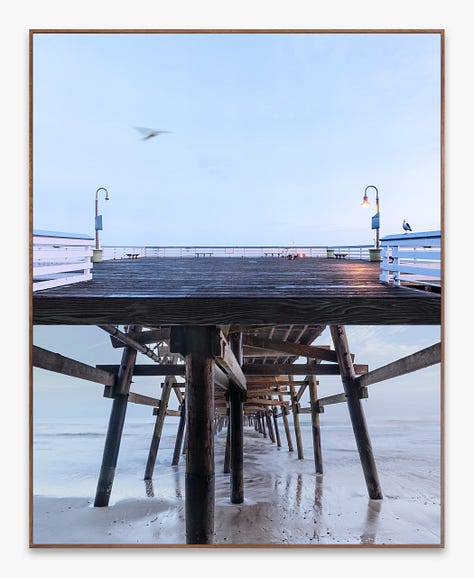

Come back here. These photographs each depict piers on the coast of California. Sort of. What they actually show, which the vast majority of photographs do not, is a compression of durational time and an expansion of physical space. They are composites. Rather than momentary captures of a particular framed view, they are layered recordings of visual information which unfold over a substantial period of time and in more than one location. Nearly always during the minutes that precede the dawn, and as the light changes quickly and dramatically, I walk to the very end of a pier and photograph from that vantage point. Sometimes, a piece of architecture stands in the way of what would otherwise be an uninterrupted gaze into the seemingly infinite ocean and sky. Sometimes not. (As a rule, I do not discriminate much between the built and the natural environments). In part because of the quiet time of day and in part because of post-production alterations, there are no people nor signage/language to rely upon for solace, familiarity, or company. There are only remnants of human presence, like an occasional fishing pole or vacant structure. I make sure the viewer of my work is left alone and undisturbed in the space. There are birds, though. There are always birds.

Using a robotic tripod head that moves precisely in an overlapping grid pattern, I make an array of dozens of detailed photographs, one by one, as time is ticking by and light is changing as fast as I can blink (usually for the worse), moving horizontally left to right and from top to bottom. During this time, birds fly or stroll in and out of frames, lamps on dusk/dawn timers turn off as natural replaces electric light, the pier rocks gently from the movement of the waves below, and all of the incredible sounds sound. Once this process is finished, which normally takes an hour or so, I pack up my gear and walk all the way back to the beginning of the pier and then hike underneath the support structure onto the sand and rocks. Using the same process as above, I make an array of photographs of the view looking through the center of the pier columns into the ocean. The movement of the crashing waves is recorded with longer exposures, soft and blurry. This process also takes about an hour. The top view and bottom view, already composites and temporally expansive in their own right, are then carefully composited together in post-production to create one initially coherent image that represents a “real” place, a “real” photograph, a “real” experience, yet of an unnatural perspective with two vanishing points and a compressed representation of a substantial passage of time.

Where are you now?

Why piers? In one sense, piers represent the furthest point of travel by foot from the continental landmass. People seem to have an existential drive and desire for a sublime experience when they voluntarily “walk the plank” for leisure rather than by coercion. During the last couple of years of the global pandemic, this longing to escape has been exacerbated for many people, including me. During a time when there has been a simultaneous jonesing to get out and get away, but nowhere to safely go and no people to safely see, traveling alone to these dozens of piers over the last 18 months has felt necessary, if only as temporary relief. Ultimately, the only place to go is here. Always.

“Built in 1904. Damaged in 1935, 1983. 1992, 1994, 2014, 2016. Restored in 1939, 1985, 1996, 2018.” The long titles of each photograph, which intentionally omit specific locations, convey an ongoing history of persistence, impermanence, and instability, not a particular place on a map. They are both documents and not-documents. These places are part of something larger that is in flux. They are part of a history that is still unfolding. They are not nouns. They are verbs. They are being. These piers are cared for and rebuilt after recurring natural and human-made disasters. It’s endearing. “Built in the year so and so, damaged in years so and so, renovated in years so and so, photographed in the year so and so.” Who knows the future fate of these resilient structures? Right now, they are all standing strong and enduring relentless erosion.

In terms of art historical context, there is clearly a nod to photographic typologies, most formally those of Bernd and Hilla Becher and Hiroshi Sugimoto. The consistent frontal point of view and the type of structure being depicted, highlighting, examining, and almost fetishizing each pier’s unique construction, is knowingly reminiscent of the Bechers. And, it’s hard not to look at a number of photographs where the sky and the ocean meet at the horizon and not consider Sugimoto’s iconic seascapes. But, the comparison to the dry and analog documentary approach of traditional typological studies is only as deep as the surface of the paper on which these photographs are printed. Oddly, but perhaps more conceptually apropos, these works share some concerns with Cubist artists of the early 20th century in that they are not records of a singular moment in space and time, where one can comfortably relish in the particularities of the way the light was just so and the placement of the camera was just so. They are much more messy and unstable and strive to represent a three-dimensional reality about movement, space, and time in two dimensions. These photographs are attempts at resuscitating corpses. I want to breathe life into them, as sappy and Sisyphean as that sounds.

Undoubtedly, the sun is rising, the moon is setting, the pier is swaying, the wood is rotting, the waves are pulsating, the birds are flying, the dolphins are swimming, the clouds are passing, the camera is capturing light, the body is breathing, and the heart is pumping. Here.

Now. What do you hear here when you peer through the pier?

The text above is narrated by me in the video below, with the added benefit of seeing the images.

Lovely explanations and art! Reminds me of the opening stanza of Szymborska's "nothing twice": Nothing can ever happen twice.

In consequence, the sorry fact is

that we arrive here improvised

and leave without the chance to practice.